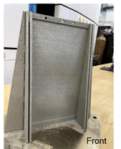

It is some months since I have written about engineering so this post is focussed on some mechanical engineering. The advent of pneumatic and electric torque wrenches has made it impossible for the ordinary motorist to change a wheel because it is very difficult to loosen wheel nuts by hand when they have been tightened by a powered wrench which most of us do not have available. This has probably made motoring safer but also means we are more likely to need assistance when we have a flat tire. It also means that the correct tightening pattern for nuts and bolts is less widely known. A star-shaped sequence is optimum, i.e., if you have six bolts numbered sequentially around a circle then you start with #1, move across the diameter to #4, then to #2 followed by #5 across the diameter, then to #3 and across the diameter to #6. This sequence is optimum for flanges, bolted joints in the frames of buildings and joining machine parts as well as wheel nuts. We have recently discovered that it works in reverse, in the sense that it is the optimum sequence for releasing parts made by additive manufacturing (AM) from the baseplate of the AM machine (see ‘If you don’t succeed try and try again’ on September 29th, 2021). Additive manufacturing induces large residual stresses as a consequence of the cycles of heat input to the part during manufacturing and some of these stresses are released when it is removed from the baseplate of the AM machine, which causes distortion of the part. Together with a number of collaborators, I have been researching the most effective method of building thin flat plates using additive manufacturing (see ‘On flatness and roughness’ on January 19th, 2022). We have found that building the plate vertically layer-by-layer works well when the plate is supported by buttresses on its edges. We have used two in-plane buttresses and four out-of-plane buttresses, as shown in the photograph, to achieve parts that have comparable flatness to those made using traditional methods. It turns out that optimum order for the removal of the buttresses is the same star sequence used for tightening bolts and it substantially reduces distortion of the plate compared to some other sequences. Perhaps in retrospect, we should not be surprised by this result; however, hindsight is a wonderful thing.

It is some months since I have written about engineering so this post is focussed on some mechanical engineering. The advent of pneumatic and electric torque wrenches has made it impossible for the ordinary motorist to change a wheel because it is very difficult to loosen wheel nuts by hand when they have been tightened by a powered wrench which most of us do not have available. This has probably made motoring safer but also means we are more likely to need assistance when we have a flat tire. It also means that the correct tightening pattern for nuts and bolts is less widely known. A star-shaped sequence is optimum, i.e., if you have six bolts numbered sequentially around a circle then you start with #1, move across the diameter to #4, then to #2 followed by #5 across the diameter, then to #3 and across the diameter to #6. This sequence is optimum for flanges, bolted joints in the frames of buildings and joining machine parts as well as wheel nuts. We have recently discovered that it works in reverse, in the sense that it is the optimum sequence for releasing parts made by additive manufacturing (AM) from the baseplate of the AM machine (see ‘If you don’t succeed try and try again’ on September 29th, 2021). Additive manufacturing induces large residual stresses as a consequence of the cycles of heat input to the part during manufacturing and some of these stresses are released when it is removed from the baseplate of the AM machine, which causes distortion of the part. Together with a number of collaborators, I have been researching the most effective method of building thin flat plates using additive manufacturing (see ‘On flatness and roughness’ on January 19th, 2022). We have found that building the plate vertically layer-by-layer works well when the plate is supported by buttresses on its edges. We have used two in-plane buttresses and four out-of-plane buttresses, as shown in the photograph, to achieve parts that have comparable flatness to those made using traditional methods. It turns out that optimum order for the removal of the buttresses is the same star sequence used for tightening bolts and it substantially reduces distortion of the plate compared to some other sequences. Perhaps in retrospect, we should not be surprised by this result; however, hindsight is a wonderful thing.

The current research is funded jointly by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the USA and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) in the UK and the project was described in ‘Slow start to an exciting new project on thermoacoustic response of AM metals’ on September 9th 2020.

Image: Photograph of a geometrically-reinforced thin plate (230 x 130 x 1.2 mm) built vertically layer-by-layer using the laser powder bed fusion process on a baseplate (shown removed from the AM machine) with the supporting buttresses in place.

Sources:

Patterson EA, Lambros J, Magana-Carranza R, Sutcliffe CJ. Residual stress effects during additive manufacturing of reinforced thin nickel–chromium plates. IJ Advanced Manufacturing Technology;123(5):1845-57, 2022.

Khanbolouki P, Magana-Carranza R, Sutcliffe C, Patterson E, Lambros J. In situ measurements and simulation of residual stresses and deformations in additively manufactured thin plates. IJ Advanced Manufacturing Technology; 132(7):4055-68, 2024.