Feedback on students’ assignments is a challenge for many in higher education. Students appear to be increasingly dissatisfied with it and academics are frustrated by its apparent ineffectiveness, especially when set against the effort required for its provision. In the UK, the National Student Survey results show that satisfaction with assessment and feedback is increasing but it remains the lowest ranked category in the survey [1]. My own recent experience has been of the students’ insatiable hunger for feedback on a continuing professional development (CPD) programme, despite receiving detailed written feedback and one-to-one oral discussion of their assignments.

Feedback on students’ assignments is a challenge for many in higher education. Students appear to be increasingly dissatisfied with it and academics are frustrated by its apparent ineffectiveness, especially when set against the effort required for its provision. In the UK, the National Student Survey results show that satisfaction with assessment and feedback is increasing but it remains the lowest ranked category in the survey [1]. My own recent experience has been of the students’ insatiable hunger for feedback on a continuing professional development (CPD) programme, despite receiving detailed written feedback and one-to-one oral discussion of their assignments.

So, what is going wrong? I am aware that many of my academic colleagues in engineering do not invest much time in reading the education research literature; perhaps because, like the engineering research literature, much of it is written in a language that is readily appreciated only by those immersed in the subject. So, here is an accessible digest of research on effective feedback that meets students’ expectations and realises the potential improvement in their performance.

It is widely accepted that feedback is an essential component [2] in the learning cycle and there is evidence that feedback is the single most powerful influence on student achievement [3, 4]. However, we often fail to realise this potential because our feedback is too generic or vague, not sufficiently timely [5], and transmission-focussed rather than student-centered or participatory [6]. In addition, our students tend not to be ‘assessment literate’, meaning they are unfamiliar with assessment and feedback approaches and they do not interpret assessment expectations in the same way as their tutors [5, 7]. Student reaction to feedback is strongly related to their emotional maturity, self-efficacy and motivation [1]; so that for a student with low self-esteem, negative feedback can be annihilating [8]. Emotional immaturity and assessment illiteracy, such as is typically found amongst first year students, is a toxic mix that in the absence of a supportive tutorial system leads to student dissatisfaction with the feedback process [1].

So, how should we provide feedback? I provide copious detailed comments on students’ written work following the example of my own university tutor, who I suspect was following example of his tutor, and so on. I found these comments helpful but at times overwhelming. I also remember a college tutor who made, what seemed to me, devastatingly negative comments about my writing skills, which destroyed my confidence in my writing ability for decades. It was only restored by a Professor of English who recently complimented me on my writing; although I still harbour a suspicion that she was just being kind to me. So, neither of my tutors got it right; although one was clearly worse than the other. Students tend to find negative feedback unfair and unhelpful, even when it is carefully and politely worded [8].

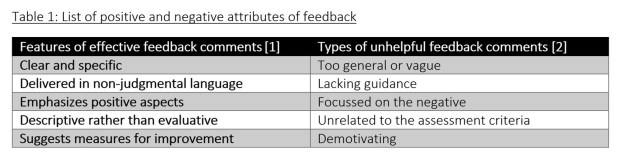

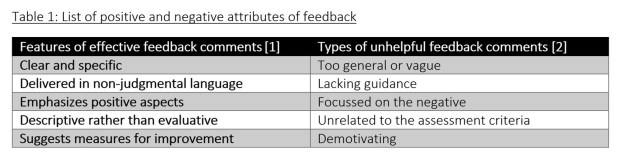

Students like clear, unambiguous, instructional and direction feedback [8]. Feedback should provide a statement of student performance and suggestions for improvement [9], i.e. identify the gap between actual and expected performance and provide instructive advice on closing the gap. This implies that specific assessment criteria are required that explicitly define the expectation [2]. The table below lists some of the positive and negative attributes of feedback based on the literature [1,2]. However, deploying the appropriate attributes does not guarantee that students will engage with feedback; sometimes students fail to recognise that feedback is being provided, for example in informal discussion and dialogic teaching; and hence, it is important to identify the nature and purpose of feedback every time it is provided. We should reduce our over-emphasis on written feedback and make more use of oral feedback and one-to-one, or small group, discussion. We need to take care that the receipt of grades or marks does not obscure the feedback, perhaps by delaying the release of marks. You could ask students about the mark they would expect in the light of the feedback; and, you could require students to show in future work how they have used the feedback – both of these actions are likely to improve the effectiveness of feedback [5].

In summary, feedback that is content rather than process-driven is unlikely to engage students [10]. We need to strike a better balance between positive and negative comments, which includes a focus on appropriate guidance and motivation rather than justifying marks and diagnosing short-comings [2]. For most of us, this means learning a new way of providing feedback, which is difficult and potentially arduous; however, the likely rewards are more engaged, higher achieving students who might appreciate their tutors more.

References

[1] Pitt E & Norton L, ‘Now that’s the feedback that I want!’ Students reactions to feedback on graded work and what they do with it. Assessment & Evaluation in HE, 42(4):499-516, 2017.

[2] Weaver MR, Do students value feedback? Student perceptions of tutors’ written responses. Assessment & Evaluation in HE, 31(3):379-394, 2006.

[3] Hattie JA, Identifying the salient facets of a model of student learning: a synthesis of meta-analyses. IJ Educational Research, 11(2):187-212, 1987.

[4] Black P & Wiliam D, Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1):7-74, 1998.

[5] O’Donovan B, Rust C & Price M, A scholarly approach to solving the feedback dilemma in practice. Assessment & Evaluation in HE, 41(6):938-949, 2016.

[6] Nicol D & MacFarlane-Dick D, Formative assessment and self-regulatory learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in HE, 31(2):199-218, 2006.

[7] Price M, Rust C, O’Donovan B, Handley K & Bryant R, Assessment literacy: the foundation for improving student learning. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, 2012.

[8] Sellbjer S, “Have you read my comment? It is not noticeable. Change!” An analysis of feedback given to students who have failed examinations. Assessment & Evaluation in HE, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1310801, 2017.

[9] Saddler R, Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in HE, 35(5):535-550, 2010.

[10] Hounsell D, Essay writing and the quality of feedback. In J Richardson, M. Eysenck & D. Piper (eds) Student learning: research in education and cognitive psychology. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1987.