As children many of us have burnt a hole (yes, tenuous link to last week’s post on ‘Holes’) in a piece of paper by focussing the sun’s rays with a magnifying glass. If you move the glass up or down and tilt it slightly then the sun’s rays will not be focussed on a spot and instead you see a complex spiralling pattern of light. This pattern is caused by the rays being bent by their passage through different sections of the curved glass. The same type of pattern, known as a caustic, appears on the bottom of your bath when you let (clean) water run out down the plug-hole if you have spotlights above the bath. This caustic is produced by the light rays from the spotlight being bent by varying degrees depending on where they pass through the vortex formed by the water spinning down the hole. Caustics can also be produced when light passes through a glass of water or on the bottom of an outdoor swimming pool in bright sunlight.

The top picture shows the caustic formed by light passing through a transparent plate with a hole when the plate is stretched in the vertical direction. The load in the plate has to flow around the hole where it ‘bunches up’ or concentrates (see last week’s post entitled ‘Holes’) which causes high levels of local deformation with the plate thinning non-linearly at the intersection of the hole circumference and horizontal diameter. When the light passes through the deformed region it is deviated by amount dependent on the local thinning and forms the pattern shown.

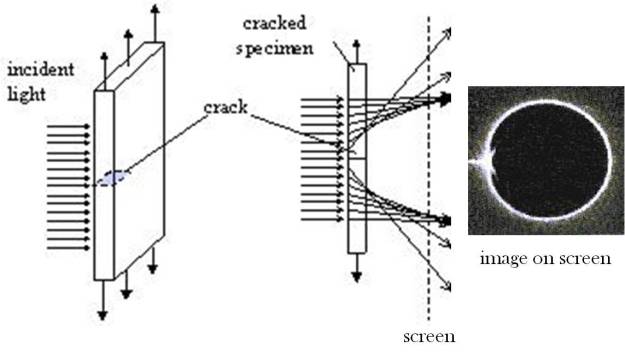

This is not a totally abstract phenomenon because the same mechanism of thinning occurs at the tip of cracks as a result of the very high stress concentration at the sharp crack tip, as shown schematically in the diagram below. So we can evaluate the stress concentration by measuring the caustic it generates; it is even possible to predict in which direction the crack will grow next.

Schematic diagram of transparent plate with a crack loaded vertically in tension (left), light ray tracings through the cracked region (centre) and caustic formed on a screen (right).

For information: