Each year in my thermodynamics class I have some fun popping balloons and talking about irreversibilities that occur in order to satisfy the second law of thermodynamics. The popping balloon represents the unconstrained expansion of a gas and is one form of irreversibility. Other irreversibilities, including friction and heat transfer, are discussed in the video clip on Entropy in our MOOC on Energy: Thermodynamics in Everyday Life which will rerun from October 3rd, 2016.

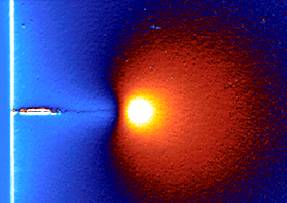

Last week I was in Florida at the Annual Conference of the Society for Experimental Mechanics (SEM) and Clive Siviour, in his JSA Young Investigator Lecture, used balloon popping to illustrate something completely different. He was talking about the way high-speed photography allows us to see events that are invisible to the naked eye. This is similar to the way a microscope reveals the form and structure of objects that are also invisible to the naked eye. In other words, a high-speed camera allows us to observe events in the temporal domain and a microscope enables us to observe structure in the spatial domain. Of course you can combine the two technologies together to observe the very small moving very fast, for instance blood flow in capillaries.

Clive’s lecture was on ‘Techniques for High Rate Properties of Polymers’ and of course balloons are polymers and experience high rates of deformation when popped. He went on to talk about measuring properties of polymers and their application in objects as diverse as cycle helmets and mobile phones.