The holes that I wrote about last week and the week before (post entitled ‘Holes‘ on October 8th)were essentially air-filled holes in a solid plate. When an in-plane load is applied to the plate it deforms and its surface around the hole becomes curved due to the concentration of stress and light passing through the curved surfaces is deviated to form the caustic. If you didn’t follow that quick recap on last week then you might want flip back to last week’s post before pressing on!

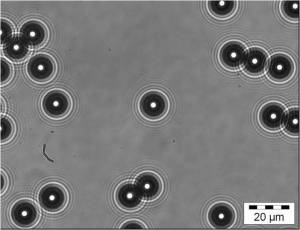

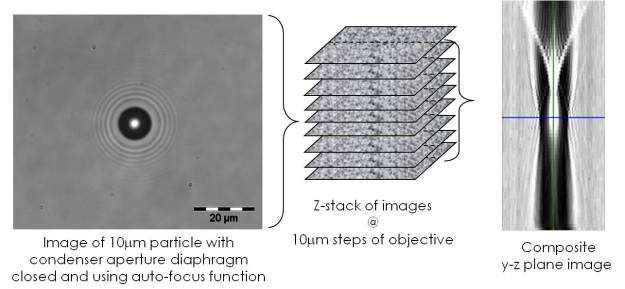

The reverse situation is a solid in a fluid. It is difficult to induce stress in a fluid so instead we can use a three-dimensional hole, i.e. a sphere, to generate the curve surface for light to pass through and be deviated. This is quite an easy experiment to do in an optical microscope with some polystyrene spheres floating in distilled water with the microscope slightly out of focus you get bright caustics. And if you take a series of photographs (the x-y plane) with the microscope objective lens at different heights (z-value) it is possible to reconstruct the three-dimensional shape of the caustic by taking the intensity or greyscale values along the centre line of each image and using them all to create new image of the x-z and, or y-z plane, as shown in the picture.

Well done if you have got this far and are still with me! I hope you can at least enjoy the pictures. By the way the particle in the images is about the same diameter as a human hair.

Image in optical microscope of polystyrene particle in water (left), series of images at different positions of microscope objective (centre) and artificial image created from greyscale data along centre-lines of image series (right).

Source: