In his recent book, ‘The Place of Tides’, James Rebanks writes ‘the age of humans will pass. Perhaps the end has already begun though it may take a long time to play out’. I grew up when nuclear armageddon appeared to be the major threat to the future of life on Earth and it remains a major threat, especially given current tensions between nations. However, other threats have gained prominence including both a massive asteroid impact, on the scale of the one that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, and climate change, which caused the largest mass extinction, killing 95% of all species, about 252 million years ago. The current extinction rate is between 100 and 1000 times greater than the natural rate and is being driven by the overexploitation of the Earth’s resources by humans leading to habitat destruction and climate change. Humans are part of a complex ecosystem, or system of systems, including soil systems with interactions between microorganisms, plants and decaying matter; pollination systems characterised by co-dependence between plants and pollinators; and, aquatic systems connecting rivers, lakes and oceans by the movement of water, nutrients and migratory species. The overexploitation of these systems to support our 21st century lifestyle is starting to cause systemic failures that are the underlying cause of the increasing rate of species extinction and it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict when it will be our turn. In his 1936 book, ‘Where Life is Better: An Unsentimental American Journey’, James Rorty observes that the most dangerous fact he has come across is ‘the overwhelming fact of our lazy, irresponsible, adolescent inability to face the truth or tell it’. Not much has changed in nearly one hundred years, except that the global population has increased fourfold from about 2.2 billion to 8.2 billion with a corresponding increase in the exploitation of the Earth for energy, food and satisfying our materialistic desires. A recent exhibition at the Design Museum in London, encouraged us to think beyond human-centred design and to consider the impact of our designs on all the species on the planet. A process sometimes known as life-centred design or interspecies design. What if designs could help other species to flourish, as well as humans?

In his recent book, ‘The Place of Tides’, James Rebanks writes ‘the age of humans will pass. Perhaps the end has already begun though it may take a long time to play out’. I grew up when nuclear armageddon appeared to be the major threat to the future of life on Earth and it remains a major threat, especially given current tensions between nations. However, other threats have gained prominence including both a massive asteroid impact, on the scale of the one that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, and climate change, which caused the largest mass extinction, killing 95% of all species, about 252 million years ago. The current extinction rate is between 100 and 1000 times greater than the natural rate and is being driven by the overexploitation of the Earth’s resources by humans leading to habitat destruction and climate change. Humans are part of a complex ecosystem, or system of systems, including soil systems with interactions between microorganisms, plants and decaying matter; pollination systems characterised by co-dependence between plants and pollinators; and, aquatic systems connecting rivers, lakes and oceans by the movement of water, nutrients and migratory species. The overexploitation of these systems to support our 21st century lifestyle is starting to cause systemic failures that are the underlying cause of the increasing rate of species extinction and it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict when it will be our turn. In his 1936 book, ‘Where Life is Better: An Unsentimental American Journey’, James Rorty observes that the most dangerous fact he has come across is ‘the overwhelming fact of our lazy, irresponsible, adolescent inability to face the truth or tell it’. Not much has changed in nearly one hundred years, except that the global population has increased fourfold from about 2.2 billion to 8.2 billion with a corresponding increase in the exploitation of the Earth for energy, food and satisfying our materialistic desires. A recent exhibition at the Design Museum in London, encouraged us to think beyond human-centred design and to consider the impact of our designs on all the species on the planet. A process sometimes known as life-centred design or interspecies design. What if designs could help other species to flourish, as well as humans?

References:

Rebanks, James, The place of tides, London: Penguin, 2025.

Rorty, James, Where life is better: an unsentimental journey. New York, Reynal & Hitchcock, 1936. (I have not read this book but it was quoted by Joanna Pocock in ‘Greyhound’, Glasgow: Fitzcarraldo Editions, HarperCollins Publishers, 2025, which I have read and enjoyed).

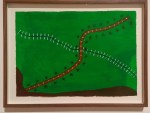

Image: Photograph of Pei yono uhutipo (Spirit of the path) by Sheraonawe Hakihiiwe, a member of the Yanomami Indigenous community who live in the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazon. One of a series of his paintings in the ‘More than Human‘ exhibition at the Design Museum which form part of an archive of Yanomami knowledge that reflects the abundance of life in the forest.