It seems unlikely that global warming will be limited to only 1.5 degrees Centigrade above pre-industrial levels in the light of recent trends in temperature data [see ‘It was hot in June and its getting hotter’ on July 12th, 2023 ]. It is probable global warming will lead to average surface temperatures on the planet rising by 4 or 5 degrees, perhaps within a matter of decades. A global average temperature rise of only 2 degrees would make the Earth as warm as it was 3 million years ago when sea levels were 25 to 35 m (80 to 130 ft) high (Blockstein & Wiegman, 2010). While it is still important to aim for zero carbon emissions in order to limit global warming and avoid global temperatures reaching a tipping point, it seems improbable that politicians worldwide will be able to agree and implement effective actions to achieve the goal in part because of the massive, vested interests in industrialised economies based on fossil fuels [see ‘Are we all free-riders?’ On April 6th, 2016]. Hence, we need to start planning for potentially existential changes in the climate and environment that will force us to adapt the way we live and work. In addition to rises in sea levels, a world that is 4 degrees hotter is likely to have an equatorial belt with high humidity causing heat stress across tropical regions that make them uninhabitable for most of the year. To the north and south of this equatorial belt will be mid-latitude belts of inhospitable deserts extending as far north as a line through Liverpool, Manchester, Hamburg, the straits north of Sapporo in Japan, Prince Rupert in British Columbia and Waskaganish on the Hudson Bay. The habitable zones for humans are likely to be north of this line and in the south in Antarctica, Patagonia, Tasmania and the south island of New Zealand. Agriculture will probably be viable in these polar regions but will compete with a very dense population [see ‘Belts of habitability in a 4° world’ in Nomad Century by Gaia Vince]. In other words, there will likely be mass migrations that will force a re-organisation of society and a restructuring of our economies. Some estimates suggest that there could be as many as 1.2 billion environmental migrants by 2050 (Bellizzi et al, 2023). We need to start adapting now, the world around us is already adapting [see ‘Collaboration and competition’ on June 8th, 2022].

It seems unlikely that global warming will be limited to only 1.5 degrees Centigrade above pre-industrial levels in the light of recent trends in temperature data [see ‘It was hot in June and its getting hotter’ on July 12th, 2023 ]. It is probable global warming will lead to average surface temperatures on the planet rising by 4 or 5 degrees, perhaps within a matter of decades. A global average temperature rise of only 2 degrees would make the Earth as warm as it was 3 million years ago when sea levels were 25 to 35 m (80 to 130 ft) high (Blockstein & Wiegman, 2010). While it is still important to aim for zero carbon emissions in order to limit global warming and avoid global temperatures reaching a tipping point, it seems improbable that politicians worldwide will be able to agree and implement effective actions to achieve the goal in part because of the massive, vested interests in industrialised economies based on fossil fuels [see ‘Are we all free-riders?’ On April 6th, 2016]. Hence, we need to start planning for potentially existential changes in the climate and environment that will force us to adapt the way we live and work. In addition to rises in sea levels, a world that is 4 degrees hotter is likely to have an equatorial belt with high humidity causing heat stress across tropical regions that make them uninhabitable for most of the year. To the north and south of this equatorial belt will be mid-latitude belts of inhospitable deserts extending as far north as a line through Liverpool, Manchester, Hamburg, the straits north of Sapporo in Japan, Prince Rupert in British Columbia and Waskaganish on the Hudson Bay. The habitable zones for humans are likely to be north of this line and in the south in Antarctica, Patagonia, Tasmania and the south island of New Zealand. Agriculture will probably be viable in these polar regions but will compete with a very dense population [see ‘Belts of habitability in a 4° world’ in Nomad Century by Gaia Vince]. In other words, there will likely be mass migrations that will force a re-organisation of society and a restructuring of our economies. Some estimates suggest that there could be as many as 1.2 billion environmental migrants by 2050 (Bellizzi et al, 2023). We need to start adapting now, the world around us is already adapting [see ‘Collaboration and competition’ on June 8th, 2022].

Tag Archives: sea level

Ice caps losing water and gravitational attraction

I have written previously about sea level rises [see ‘Merseyside Totemy‘ on August 17th, 2022 and ‘Climate change and tides in Liverpool‘ on May 11th, 2016] and the fact that a 1 metre rise in sea level would displace 145 million people [see ‘New Year resolution‘ on December 31st, 2014]. Sea levels globally have risen 102.5 mm since 1993 primarily due to the water added as a result of the melting of glaciers and icecaps and due to the expansion of the seawater as its temperature rises – both of these causes are a result of global warming resulting from human activity. I think that this is probably well-known to most readers of this blog. However, I had not appreciated that the polar ice caps are sufficiently massive that their gravitational attraction pulls the water in the oceans towards them, so that as they melt the oceans move towards a more even distribution of water raising sea levels further away from the icecaps. This is problematic because the population density is higher in the regions further away from the polar ice caps, as shown in the image. Worldwide about 1 billion people, or about an eighth of the global population, live less than 10 metres above current high tide lines. If we fail to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Centigrade and it peaks at 5 degrees Centigrade then the average sea level rise is predicted to be as high as 7 m according to the IPCC.

I have written previously about sea level rises [see ‘Merseyside Totemy‘ on August 17th, 2022 and ‘Climate change and tides in Liverpool‘ on May 11th, 2016] and the fact that a 1 metre rise in sea level would displace 145 million people [see ‘New Year resolution‘ on December 31st, 2014]. Sea levels globally have risen 102.5 mm since 1993 primarily due to the water added as a result of the melting of glaciers and icecaps and due to the expansion of the seawater as its temperature rises – both of these causes are a result of global warming resulting from human activity. I think that this is probably well-known to most readers of this blog. However, I had not appreciated that the polar ice caps are sufficiently massive that their gravitational attraction pulls the water in the oceans towards them, so that as they melt the oceans move towards a more even distribution of water raising sea levels further away from the icecaps. This is problematic because the population density is higher in the regions further away from the polar ice caps, as shown in the image. Worldwide about 1 billion people, or about an eighth of the global population, live less than 10 metres above current high tide lines. If we fail to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Centigrade and it peaks at 5 degrees Centigrade then the average sea level rise is predicted to be as high as 7 m according to the IPCC.

Image: Population Density, v4.11, 2020 by SEDACMaps CC-BY-2.0 Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Source: Thomas Halliday, Otherlands: A World in the Making, London: Allen Lane, 2022

Merseyside Totemy

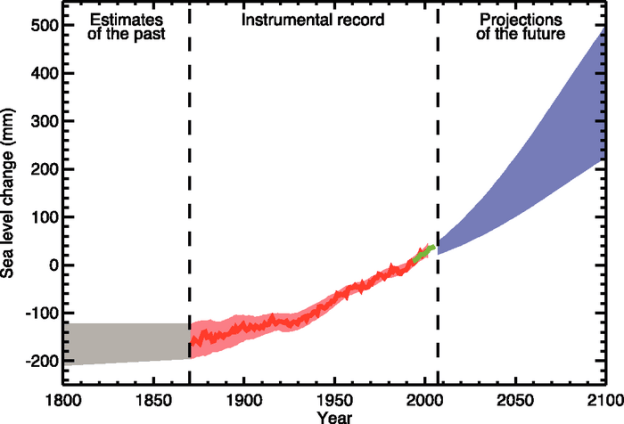

The recent extreme weather is perhaps leading more people to appreciate the changes in our climate are real and likely to have a serious impact on our way of life [see ‘Climate change and tides in Liverpool‘ on May 11th, 2016]. However, I suspect that most people do not appreciate the likely catastrophic effect of global warming. For example, during the 20th century, the average rise is sea level was 1.7 mm per year; however, since the early 1990s it has been rising at 3 mm per year, and sea levels are currently rising at about 4mm per year according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It is difficult to translate statistics of this type into a meaningful format – the graph below helps in recognising the trends but does not convey anything about the impact. However, I am impressed by a new art installation on the Liverpool waterfront by Alicja Biala called ‘Merseyside Totemy’ which illustrates the percentage of each of three high-risk local areas that will be underwater by 2080 if current trends continue: Birkenhead (centre of photograph), Formby (left) and Liverpool City Centre (right behind tree) [see www.biennial.com/collaborations/alicjabiala]. Perhaps using data for 30 years time rather than 60 years would have focussed people’s attention on the need to make changes to alleviate the impact.

The recent extreme weather is perhaps leading more people to appreciate the changes in our climate are real and likely to have a serious impact on our way of life [see ‘Climate change and tides in Liverpool‘ on May 11th, 2016]. However, I suspect that most people do not appreciate the likely catastrophic effect of global warming. For example, during the 20th century, the average rise is sea level was 1.7 mm per year; however, since the early 1990s it has been rising at 3 mm per year, and sea levels are currently rising at about 4mm per year according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It is difficult to translate statistics of this type into a meaningful format – the graph below helps in recognising the trends but does not convey anything about the impact. However, I am impressed by a new art installation on the Liverpool waterfront by Alicja Biala called ‘Merseyside Totemy’ which illustrates the percentage of each of three high-risk local areas that will be underwater by 2080 if current trends continue: Birkenhead (centre of photograph), Formby (left) and Liverpool City Centre (right behind tree) [see www.biennial.com/collaborations/alicjabiala]. Perhaps using data for 30 years time rather than 60 years would have focussed people’s attention on the need to make changes to alleviate the impact.

Figure 1. Time series of global mean sea level (deviation from the 1980-1999 mean) in the past and as projected for the future. For the period before 1870, global measurements of sea level are not available. The grey shading shows the uncertainty in the estimated long-term rate of sea level change. The red line is a reconstruction of global mean sea level from tide gauges, and the red shading denotes the range of variations from a smooth curve. The green line shows global mean sea level observed from satellite altimetry. The blue shading represents the range of model projections for the SRES A1B scenario for the 21st century, relative to the 1980 to 1999 mean, and has been calculated independently from the observations. Beyond 2100, the projections are increasingly dependent on the emissions scenario. Over many centuries or millennia, sea level could rise by several metres. From https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-5-1-figure-1.html